For the past two years or so, the Russian Air Force has been using glider bombs developed from ordinary drop bombs in Ukraine and deployed by aircraft that release them in relative safety from Ukrainian anti-aircraft defences, generally deployed deeper against ballistic and cruise missiles, and kamikaze UAVs on the other. Compared to these threats, however, glider bombs represent cheaper, more expeditious, and certainly easier to produce alternatives, since they are modifications on existing munitions.

The UMPK kits have played an important role in destroying many Ukrainian fortified positions with almost complete impunity. It has been calculated that for months now, the Russians have been able to launch an average of between 40 and 50 glider bombs per day, and sometimes up to 80, with some cases even reaching around 150-200 in a single day.

Known by the generic name of UMPK (Unifitsirovannogo Nabora Modulei Planirovanie i Korekcii, more or less translatable as ‘unified complex of planing and correction modules’), such devices are often reported as the counterpart of the Western JDAMs. In reality, compared to these, many of the UMPKs are not guided!

Their purpose is limited to extending the distance of the ordnance's release from the supposed target, so as to keep the airborne platform out of the range of Ukrainian tactical anti-aircraft defences deployed for immediate frontline protection. In more recent months, however, several attempts have emerged in the form of unexploded ordnance found by the Ukrainians to install satellite guidance devices and associated mobile guidance surfaces, with the clear intention of giving the modified bombs employment characteristics closer to those of JDAMs.

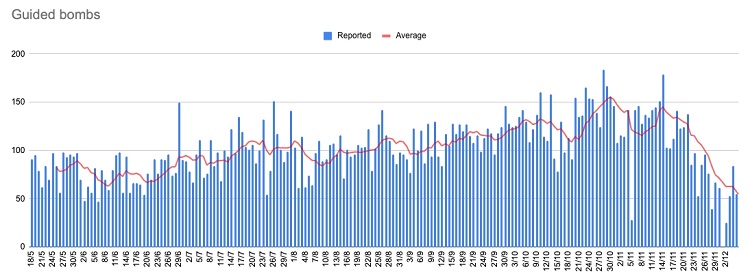

However, the UMPKs have by no means turned out to be the ‘game changer’ that some analysts and commentators expected. On the contrary, the following graph shows how, in the most recent months, a marked decline in their use has been observed (N.B. although the graph states ‘guided bombs’, in reality, only a fraction of them actually have a real guidance system, at least in the sense of ‘smart PGMs’)

The trend, as can be seen from the graph, is relative to 2024, and the winter months of that year (which amounted, roughly, to about 600 UMPK) show an average that is still higher than the same months of 2023 (which amounted to about 500 bombs). Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the most recent trend observes a downward trend, particularly from mid-November 2024.

Some attribute this to winter weather, as it certainly decreases the effectiveness of reconnaissance drones, which are an integral part of the UMPK targeting cycle. In effect, it is well known that some Russian ISR drone models are rather ‘sensitive’ to winter temperatures. Moreover, Ukrainian countermeasures against reconnaissance drones have greatly improved, both kinetic (mobile anti-aircraft batteries, ‘slow mover interceptors’ drone-killers, and recently also FPV anti-drone fighters) and in terms of electronic warfare. We believe that the effects of the Ukrainian indirect approach strategy focused on the destruction of fuel depots and refineries, which many have interpreted as aimed at influencing Russian export prices of such commodities, are beginning to be felt.

This view has never been entirely convincing and, in fact, and we have always believed that the ultimate purpose of attacks of this kind has always been to impact the availability of aviation fuel and lubricants. Thus, the purpose of ‘crippling’ the Russian Air Force well before taking-off for UMPK drop missions is evident - since these are almost impossible for the Ukrainian anti-aircraft defences and air force to intercept due to the distance at which glider bombs can be launched.

Finally, we must notice that the declining trend in question is quite overlapping with the decision, dating back to mid-November 2024, of certain Western allies to allow the deployment of ATACMS ballistic missiles and STORM SHADOW/SCALP cruise missiles deep inside Russian territory. As is well known, several airbases (and even a few depots/assembly points for UMPK kits on the ‘dumb’ ordnance) were engaged following the green light. Missile attacks took place at the same time as even larger waves of Ukrainian long-range drone raids against Russian military airfields. This has resulted in the redeployment of many Russian Air Force units to extensively backward bases.

As a result, aircraft, pilots and ordnance are less likely to be engaged by the Ukrainian offensive, or the aircraft are nevertheless forced to carry a smaller war load, as some pylons have to be used for additional tanks or remain empty to save weight (and fuel consumption) on the aircraft.

In addition, the missions themselves take longer, resulting in fewer overall sorties per day. Therefore, there is no single reason behind the decline in the use of UMPKs, but a number of factors that, as we have seen, lie between the structural and the contingent. These include the winter months and/or the continued existence of Ukrainian counter-drone capabilities. Should these somehow come to an end (and winter, at least, certainly ends sooner or later), Russia could perhaps resume the use of UMPKs on a large scale, unless the other more structural factors we have indicated become so cogent as to seriously damage the Russian Air Force's operational capability.

Follow us on Telegram, Facebook and X.