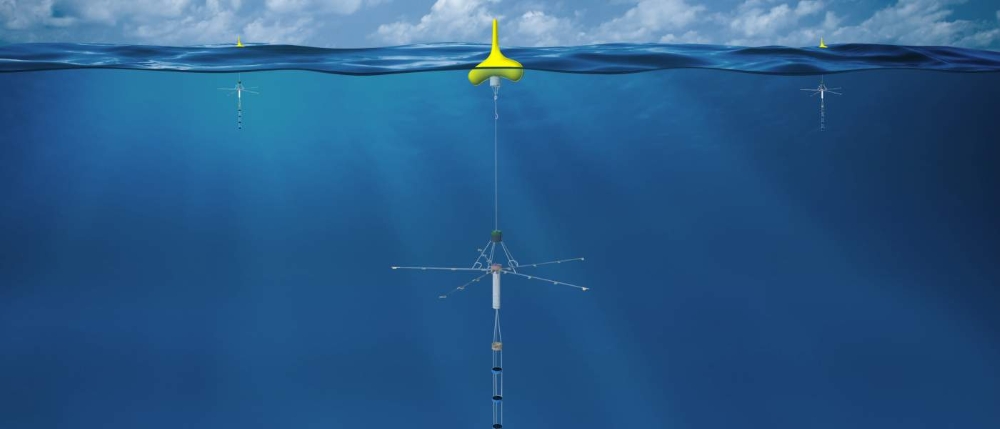

A new medium-frequency sonobuoy now emerging from Advanced Acoustic Concepts (AAC) and Thales promises to change how air and maritime forces hunt submarines. The Medium-Frequency Combination Active Passive Sonobuoy (MCAPS) is pitched as the first buoy to combine full active and passive acoustic capability in a single form factor, while tripling detection range compared with legacy systems. In an era of ever-quieter submarines, contested littorals and finite budgets, that blend of reach, flexibility and efficiency speaks directly to the US Navy’s most pressing anti submarine warfare (ASW) requirements – and, by extension, to NATO and allied fleets facing the same undersea challenge.

For more than 40 years, the US Navy has relied on a mixed inventory of sonobuoys: passive receivers and active transmitters, fielded in combinations tailored to mission and threat. Despite incremental improvements in sensitivity and processing, the basic concept has changed little. Buoys tend to be single role, coverage is constrained by range, and the result is high consumption: the US Navy deploys around 250,000 buoys annually, more than all other nations combined.

According to recently released company literature, MCAPS has been conceived as a direct response to this model’s limitations. Instead of deploying separate active and passive fields, MCAPS integrates both functions into one buoy. A modern medium frequency transducer, an enhanced receive array and a next generation battery system underpin a claimed threefold increase in detection range over current types, while also delivering a narrow band passive mode comparable to the AN/SSQ 53 DIFAR – but with greater reach.

The development pathway is the result of both operational and industrial priorities. Advanced Acoustic Concepts, working with Thales Underwater Systems, is preparing to bring series production into the United States at scale, in order to meet the Navy’s day to day usage and war reserve inventory needs. Candidate US manufacturing sites are being evaluated, with an eye to expanding production capacity, creating technical jobs and reinforcing a more resilient domestic supply chain for critical undersea warfare consumables. At the same time, the design conforms to NATO standards to enable interchangeability and cooperative employment with allied and partner navies. That positions MCAPS also as a potential common sonobuoy family for coalition ASW operations.

Technology challenges: doing more in a single canister

Folding genuine active and passive performance into one A size sonobuoy brings several technical challenges. First is the acoustic compromise. Active and passive modes traditionally drive different design choices in areas such as transducer geometry, frequency band, array layout and signal processing. MCAPS has to support both Continuous Active Sonar (CAS) and traditional single pulse transmissions, while still delivering a credible narrow band passive capability. Achieving useful source levels for CAS, maintaining waveform fidelity and then switching to a sensitive passive receive mode, all within the power and volume limits of a standard buoy, is non trivial.

Power management is the second major hurdle. CAS and long range active search are power hungry by definition. MCAPS relies on a new battery system to sustain its expanded mission set and enlarged detection envelope. That implies careful optimisation of duty cycles, waveform design and onboard processing to ensure endurance is not sacrificed for raw performance.

Third, integration of advanced processing is essential. Continuous active sonar especially demands sophisticated detection, tracking and classification algorithms to deal with reverberation, clutter and target motion in complex littoral environments. Pushing some of that processing to the buoy – rather than relying entirely on aircraft or shipboard systems – raises additional design complexity but can reduce the data burden on already busy ASW platforms.

Finally, environmental robustness and reliability remain perennial issues. A “do more with less” buoy only delivers value if it can be trusted in volume production and across a wide range of operating conditions. For a fleet that burns through a quarter of a million units per year, manufacturing repeatability and quality control are as important as the underlying acoustic physics.

Impact on ASW tactics and strategy

If MCAPS meets its performance claims, its impact on ASW tactics could be considerable. The most immediate effect is on field design and mission planning. Because each MCAPS unit provides both active and passive sensing, aircrews can build fields that are inherently multi static and multi mode without juggling separate buoy types. A single aircraft can survey a larger area with fewer stores, simplifying load planning and freeing magazine and cabin space for other payloads.

In practical terms, that enables sparser fields with comparable or better probability of detection, or denser fields with dramatically improved localisation and tracking performance. CAS waveforms offer persistent illumination and improved track continuity against manoeuvring or intermittently quiet targets, while the passive mode supports covert monitoring, classification and post detection tracking without continuous pinging.

From a stand off and survivability perspective, extended detection ranges allow maritime patrol aircraft and helicopters to operate further from suspected submarine positions, complicating counter air and anti access efforts by potential adversaries. Longer range cueing, combined with fewer required buoys, also reduces time spent in high threat areas to seed a given barrier or search box.

Strategically, the system plays directly into the need for scalable, coalition ready ASW. NATO compatibility opens the door to mixed fields seeded and exploited by different nations’ aircraft and ships, with MCAPS acting as a common sensor layer in combined operations. In a high end conflict, where undersea forces from multiple allies would be operating in concert, such interoperability could sharply reduce friction and accelerate the build up of an effective ASW picture.

Finally, there is a resource and readiness dimension. Doing the same job with fewer buoys or achieving a higher level of coverage with the same expenditure, eases pressure on procurement budgets and wartime stockpiles. For a Navy that consumes sonobuoys at unrivalled scale, and for allies who must balance ASW needs against other modernisation priorities, that cost efficiency is likely to be as compelling as the raw performance gains. In that sense, might represent a broader shift towards multi function, network centric undersea sensors designed for contested seas, tight budgets and coalition warfare.